towers of downtown Detroit looked unusually attractive, like some remote Xanadu, Iacocca reflected on the car that must now be thought of as Mustang I: "I've said it a hundred times and I'll say it again: The Mustang market never left us; we left it." Through two style changes it kept getting bigger and bigger. As designer Gene Bordinat put it, "We started out with a secretary-car and all of a sudden we had a behemoth on our hands." We stopped the 460 (sic, engine) in it," said Iacocca.. "but we had all the other engines in it." As Mustang and its stablemates kept ballooning in size and power, sales of ponycars peaked and then declined as buyers expressed their interest in smaller sporty cars. Was it time to stop making Mustangs? Iacocca didn't think so. "We have a 1ittle more at stake here. We couldn't very well' say that we'd phase it out. We had a hell of an incentive to go back to the original Mustang car. The three million Mustang owners have a lot of miles on their cars. They're reasonably happy with them. And then they see a little car out there that reminds them of what they had..." Three million Mustangs have been built, but many more people than that number have fallen under its spell. Considering used car sales, some five million persons have been, or are now; Mustang owners. And considering family members, at least 15 million people can be said to have had close contact with the Mustang I. Generally they were "reasonably happy.'.' Surveys showed that 80 percent of the buyers of new 1965 Mustangs were either completety or very satisfied with their cars, as opposed to the national average of 66 percent of owners who'd say the same thing. By 1969 the percentages were down to 59 and 56 respectively, but still in favor of the Mustang.

But how do you go back to the original Mustang? Doing it literally would have meant basing the new car on the Maverick, which is surprisingly close to the first Mustang in its main dimensions and drive train choices. But that wouldn't have been much of a change from what Ford already had. As part of a survey called Project 80, Ford's advanced planners were tracking the trends toward more luxury in smaller cars and the public craving for higher-quality construction. They looked at a Grabber version of the Pinto, among other things, and concluded there was room for a sporty, specialized small car in the Ford lineup.

Figures told part of the story. The planners took a look at what they call the "sporty subcompact" category. Into it they lumped all the small imported sports cars, plus cars like the Toyota Celica, the Capri, the RX-series Mazdas and the Opel Manta, and they found the sales trend skyrocketing. From 83,000 units in 1965 they jumped to 311,000 in 1972 and are estimated at 378,000 this year. Ford has a close look at that market because 110,000 of those '73 sales will be Capris. This was a market where Ford thought it could do business. But was the right car for that market necessarily named Mustang?

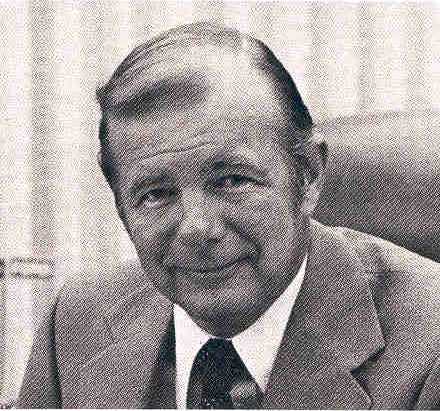

Sniffing out the right trail to follow was the Roman nose of Iacocca, unchallenged (since the departure of Bunky Knudsen) as Ford's No. 1 car man.

|

Says chief designer Bordinat: "Lee was the first guy to come along who had the feeling for cars that had existed in General Motors for some time." That feeling was telling him to think small and sporty. Iacocca: "When I look at the foreign-car market and see that one in five is a sporty car, I know something's happening. Look at what the Celica started to do before the two devaluations nailed it!" He's convinced that this is an important chunk of the market that American makers won't be able to ignore: "Anyone who decides to sit this one out just ain't gonna dance!"

Why have wallflowers GM and Chrysler left the floor wide open for Iacocca and Mustang II to strut their stuff? How come Ford, with its many-faceted Pintos, Mavericks and Capris, and now with the new Mustang II, has consistently been firstest with the mostest in the American smaller car field?

"There's no question," responds Iacocca, "that our bread-and-butter volume at Ford has always been in the smaller car. Some of it is -- I hate to use the word -- heritage. Like it or not, that's been our history. Of course I like to think that we're placed

LEFT: Lee Iacocca with his two ponies: Mustang I and the new notchback Mustang II.

ABOVE: Ben Bidwell spearheaded Lincoln-Mercury surge and now heads Ford Division.

BELOW: Even the horse has been redesigned. Mustang II, bottom, now runs at a canter.

a lot better in the rest of the market than we used to be. But I think we've got a solid slot in the small-car market. Of our total production, we run 37 to 38 small cars, and GM runs 18 percent. Now, I hope we start the era of small-car luxury and elegance."

No theme has been hammered at harder in the making of this car. Iacocca summed it up. "We wanted jo do a little car that had some class in its fits and finishes. I told 'em: Don't screw around with a lot of heavy

|

moudings!'" Bordinat: "He's badgered the hell out of us on that point." Says Bill Benton, involved in planning Mustang II before taking over the Lincoln-Mercury Division, "Iacocca will be out there in the showroom and he'll run his finger around the molding, and if it so much as scrapes him, some poor son of a gun will get it!"

This drive for what one Ford man rashly called a "jewel-like quality" even in the base Mustang II has been transmitted to Ben Bidwell, recently transplated from the L-M Division to the Ford Division general managership. "The No.1 objective of this company for this car," he said, "is better quality control. We expect to build a better car for less money than the guys on the other side of the water." One way he hopes to do it is by concentrating production in a single Dearborn plant where assembly problems can be quickly found and fixed. Another Is by designed-in quality. Window moldings are less likely to scratch the presidential fingers; body joints were critically reviewed and revised during early pilot-line assembly. Most importantly, money -- rectangular green money -- was spent to make the Mustang Il's equipment standard "a pretty high cut, ' , as Bordinat puts it.

Most of the money was put where the owner looks all day: in the interior. That was Iacocca's idea, and the man directly in charge of doing it was L. David Ash, a sports-car fan whose credentials included styling work on both the original Thunderbird and the first Mustang. He took his cue from interiors that, in his words, were "not entirely restrained European concepts like Jaguar, Rolls-Royce and Mercedes."

At Iacocca's request, Ash and his gang built a complete interior mockup that even had exterior sheet metal attached, and wheels, so it gave the feel of a real car. "It was a time-consuming property to build," remembers Ash, "but it served its purpose very well. We didn't have to go through an elaborate series of meetings to determine everything. It was all approved right there. We were on a crash basis to get it done, and it was very enthusiastically received." Well it should have been. The interior looks terrific, for the very good reason that Bill Benton gave: "There's a lot of money in there."

Ash went all-out in building the mockup. "We took a long look at what we considered the best not only in design but also in execution. In the course of it we used leather. We put everything in it that we could conceive of that connotes restrained elegance plus the get-up-and-go that says Mustang-something of a firebreather. About 90 percent of that mockup is in the top-Iine Mustang II now." Dave said a mouthful when he summed up the impression given by the interior, even in the low-buck line: "It's kind of a mini-T-bird."

That's a giveaway to the Ford philosophy that has made the Mustang, in all its guises, such a success. When the first one appeared in '64, Iacocca said he visualized it as a "poor man's T-bird," and Henry Ford II's favorite name for it-ultimately vetoed -- was T-bird II. Just like the first one, the Mustang II will be many kinds of cars to many people, but it will be at its best

|

MustangII.Org

MustangII.Org

74Ghia.com

74Ghia.com

FordPinto.com

FordPinto.com